Broken Open

“The task of art today is to bring chaos into order,” (Adorno, Minima Moralia: Reflections from a Damaged Life. 1951.)

“Perhaps in the world’s destruction it would be possible at last to see how it was made. Oceans, mountains. The ponderous counterspectacle of things ceasing to be. The sweeping waste, hydroptic and coldly secular. The silence.” (Cormac McCarthy, The Road. 2006.)

“Let’s just say I’m like a ship passing through storms, resting in ports now and then, until it’s time to continue the journey. I once told a friend that I’m just looking for an angel with a broken wing, one that couldn’t fly away,” (Jimmy Page, Jim Jerome Interview with Jimmy Page for People Magazine. 1975)

Above all, art is a gesture. It can never ever be the thing it is communicating about, interpreting or simulating. It can only be itself. And yet, that gesture, and how successfully it points towards a given idea, sensation or attitude, is what makes it substantive. In other words, its value is in how well it can reveal truth.

Swans, the continually evolving projet d’art of Michael Gira, are true, but it took me a long time to discover this. I had heard that they were infamous for driving listeners out of clubs in the early 80’s at the tail end of the No Wave scene. I had heard that their music was confrontational and abrasive. I read that their music had been having a resurgence and were on a victory lap touring off of their best work to date – a pair of double albums called “The Seer” (2012, Young God) and “To Be Kind” (2014, Young God). I also heard that seeing them live was a singular kind of religious experience. I was intimidated and yet, as curious as a child testing his own threshold for pain on the flame of a stovetop or in a brawl at the schoolyard. Swans recently played in New York City to a sold out crowd at the Bowery Ballroom. It was my second time seeing them perform. My first time was a few weeks before in Brooklyn, also to a sold-out crowd. How sadistic of me.

(Swans' 1983 debut “Filth” and their 2014 release "To Be Kind")

Swans are constantly referenced as progenitors of post-rock, drone, industrial, post-punk, et al. Michael Gira is the group’s frontman and bandleader. Swans is Michael Gira, Michael Gira is Swans. He is the group’s auteur. If you were to listen to their blunt and ugly debut “Filth” (1983, Neutral) alongside their most recent release “To Be Kind”, you will be startled at their newly expanded musicality, instrumentation and the scope of the songs. The Swans of today, doesn’t resemble its origins exactly, but is an extension and logical progression of the groundwork laid in the ‘80’s. The defining feature of their music has always been repetition and extremity. But now, they aim at an aliveness rather than nothingness, transcendence over decay and what feels like an overwhelming and unshakable truth, rather than simply the glee of punishing their audience.

The musicianship is controlled and disciplined, so much so that a musical idea might be played over and over again with no real change (other than an escalation in dynamics) for upwards of 20 minutes. This is where the tension comes across both on record and especially during the live show. Because so much of the experience of seeing them live is about enduring the ugliness of the present moment and accepting delayed gratification, when the songs actually arrive at a new musical idea, it’s like rapture. A musical approximation of the mantra: The way out is through.

This tension also comes from the attitude of the band who are so locked into the now that any interruption of their flow might provoke antagonism. At Bowery Ballroom during “The Apostate”, Gira, distracted by the flash of an iPhone in the front row, yelled to the photographer, never breaking from playing and kicked at the camera. I bet he gave her a great shot. At the previous show I attended, there was also an indiscernible confrontation between band and audience member in the front row. The intensity in the room when they play is palpable and contagious. This comes across on record too and colors any and all experience while listening.

A scene from "Raging Bull" (Martin Scorcese. 1980), an acknowledged influence on Swans.

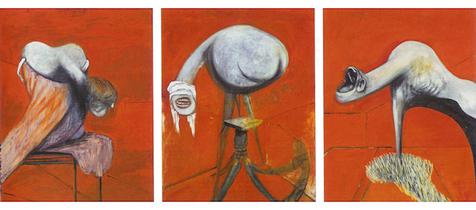

Francis Bacon's "Three Studies for Figures at the Base of a Crucifixion" (1944). Bacon is an acknowledged influence on Swans.

Francis Bacon's "Three Studies for Figures at the Base of a Crucifixion" (1944). Bacon is an acknowledged influence on Swans.

Blues legend Howlin' Wolf (date unknown), an acknowledged influence on Swans.

Blues legend Howlin' Wolf (date unknown), an acknowledged influence on Swans.

Both shows at Bowery Ballroom and Warsaw were essentially the same, from the setlist to the physical cues Gira would do during each song (swirling arms might signal the players to make a wild noise in unison, and a kick would often abruptly indicate a song’s conclusion). Both sets began with each member coming on stage one by one to the swells of Thor Harris banging a gong. Next, drummer Phil Puleo emerged and added some shimmering cymbal crescendos like waves coming in and receding. Then slide guitarist Chrisoph Hahn with the assistance of an e-bow contributed to the expanding sound. Next, bassist Christopher Pavdica, then Gira and founding member Norman Westberg armed with guitars, brought chords in and out of the cacophony with their volume dials. And after settling into a swaying and increasingly unsettling sound, a beat begins to emerge and then somehow after something like a half hour, you’ve arrived at the meat of a currently unreleased song “Frankie M.” which itself continues to buildup toward an unforeseeable, driving conclusion.

To see Gira and his bandmates slowly build towers of sound only to kick them over, is like witnessing and participating in a kind of group primal therapy. This is particularly clear on songs like “Just a Little Boy (for Chester Burnett)” where he bleats from the perspective of a child’s id. On the tremendous “Black Hole Man” which closed both shows, Gira moans with profane existential angst: “I’m an asshole man / I’m a black hole man.” That song, which explodes with dissonant sound, transforms into an uptempo bottom-heavy groove hurtling towards the same chaos that the song emerges from. It is the clearest sonic expression of these aforementioned ideas. In this way, it is obvious why Swans might appeal to the extreme music fan or the experimental music fan. Sure their brutal distorted guitar parts are produced at deafening decibel levels, but the show is something closer to an orchestral performance, abandoning the posturing and historical baggage of the guitar hero, and other rock and roll show cliches.

Swans’ music is as much about preserving a musical moment as it is about building toward a narrative arc. And yet, when you reach the end of it all, the general feeling is uplift not despair. It’s a maniacal cackle in the face of mortality, or like submerging in an ice bath after having been locked in a sauna. It is the effect of being broken open, not simply broken.

Swans press images courtesy of Young God Records.