Access Denied, Internet Dark: Technology, Prison, Education

On Sunday, April 5, an invaluable opinion piece was published in the New York Times: "Help Us Learn in Prison" by John J. Lennon. An inmate at Attica Correctional Facility in New York, Lennon makes a nuanced request about education and technology within the American prison. He considers why inmates are allowed and even encouraged to watch television all day while their access to the Internet is limited or more often than not prohibited. He ends with a plea: why not change the accessible technology of choice from TV to MOOCs?

In this post, my second for Lady Justice, I'd like to use Lennon's piece as an opportunity to continue several avenues of thinking and activism of grave concern for me, namely:

-a situated critique of MOOCs

-a situated critique of education and technology in the prison

-a situated critique of education and technology outside the prison, particularly on YouTube and social media more generally

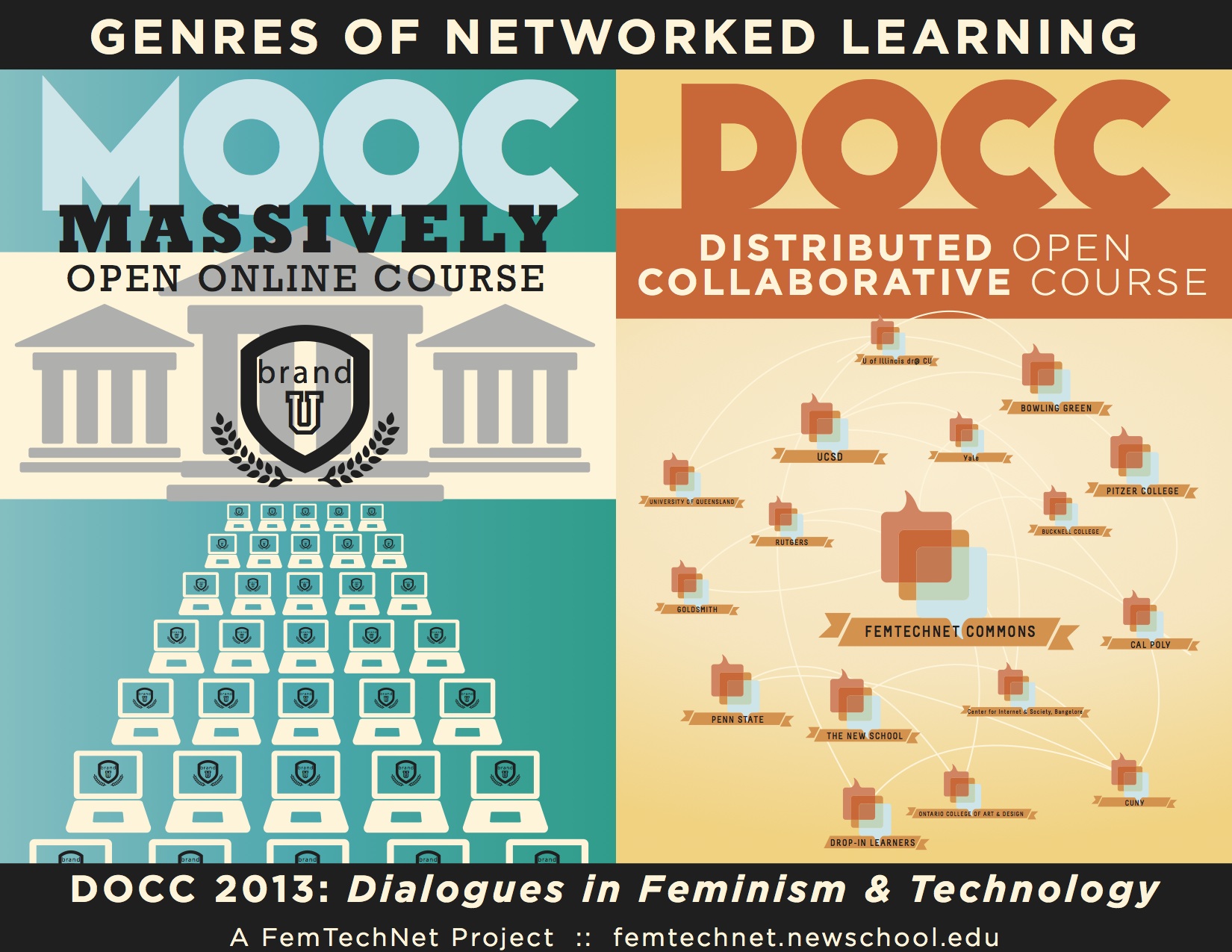

As a founding member of FemTechNet, the collective that successfully offers the DOCC (Distributed Open Collaborative Course) at places of higher learning around the world, I have worked with others to criticize MOOCs from feminist perspectives on education, technology, and neo-liberalism. One of our ongoing claims is that education needs to be situated in the lived environments of learners, whether that be institutional (are you at a community college or an art school?), regional (California or Calcutta?), cultural (what traditions and values matter where we live and learn and how do we speak about them?), or personal (what matters to me?) In their top-down, one-size-fits-all, elitist, scale-and-profit-driven underpinnings, most MOOCs are not particularly responsive to or even interested in the situated, lived differences that make learning (and teaching) both exciting and challenging.

This situated critique of MOOCs allows me to heartily second Lennon's request.

I believe that MOOCs are terrific for prisoners and support unlimited access to them as part of a technologically-assisted education.

Those who study MOOCs find that they show some real success for particular communities of learners, for example, teachers and the "highly mature, highly motivated learner who is also technologically confident." In the un(der)funded educational landscape of American prison education, these ready-made, free, open-access experiences would multiply opportunities for hungry and deprived learners in ways that could be truly revolutionary. While my situated critique still holds (prisoners learn in specific institutional, regional, cultural and personal landscapes that couldn't be farther away from the top MOOC providers, say MIT or Harvard), I believe that several of the promises of MOOCs ("the ability to access materials at any time and from any location, and the opportunity to collaborate with other learners") are uniquely empowering for prisoners, albeit with some radical technological and educational changes also required. Lennon asserts something similar. In situations like his at Attica "MOOCs could help American prisoners become more educated and connected."

Of course, accessing the promise of MOOCs depends upon other fundamental situated critiques of education and technology in prison linked to a set of concerns which Lennon begins to enumerate: "MOOCs are no substitute for the [rare] existing college programs, and no excuse not to develop them further ... they are a much-needed backup." It was this more situated critique that I learned with my inmate students at the California Rehabilitation Center at Norco last year in two classes (Technology in the Prison and Visual Culture in the Prison) that I team-taught there with students from Pitzer College and the Claremont Graduate School as part of the California-wide Prison Education Project. There are infinite, situated technologies and visual cultures in the prison (just as there are anywhere) but the particular ways that they are disciplined and controlled, and also taken up and used by prisoners, are unique in this learning environment. For example, visual messages about who can be where when dominate the visual landscape in the form of lines, signs, and bodily cues; some books are available but only after they are screened for gang-related messaging, sexuality, drug use, and profanity; the Internet is not allowed.

Naming these highly-regulated technological and visual conditions in the prison, and how they contribute to systems of institutional control and systematic oppression, became the primary foci of these two courses. The prisoner students were amazing teachers, and it was stunning to learn how the visual and technological logics of the prison are deeply connected to, if perhaps grossly exaggerated from, the underlying logics of control that operate across America. The prohibition of Internet access and the liberal favoring of television that Lennon mentions is a most egregious example of this arbitrary control that forcefully maintains logics of oppression—you can't access a MOOC, or its promise of universal access and interaction, without the Internet—but others, equally dis-enabling and utterly mundane within the prison, would include our students' arbitrary and highly controlled (in)access to pencils, paper, white boards, moving images, books, and me as their teacher.

Let me explain. In the two courses my Claremont College students and I taught in the prison, the cruel, arbitrary, changing conditions of access to education (through the administration's definitive and seemingly random control of tools, space, people, and technology) was our greatest obstacle. A piece of media might be approved through the prison's slow and strange procedures of vetting only then not to show up on the day it was on our syllabus. Teachers might volunteer and get to the prison for the weekly class only then not to be allowed into the prison because of an unexplained change in their entry status. In the most chilling of such whimsical and punitive closures of access (for me at least), my course Learning from YouTube Inside/Out—where I was planning to continue my teaching at Norco this Spring semester by building a section of this tech-focused tech-dependent class Inside with 10 inmates and 10 Claremont students albeit with quite limited access to technology—went through a lengthy and controversial approval process only to be closed down on its first day (why the class was cancelled was never explained to me or enrolled Pitzer or Norco students, but I do believe it was closely related to the proximity between my pedagogic aims and social media). I never got the chance to work through the questions which had moved me to organize this class in the first place (I write with great enthusiasm about what will happen in the course that never happened on this blog, rather chillingly in this context called Lady Justice) where I wrote:

"This year I added a "practicum" to the class. A small group of Pitzer students will be taking an extra half credit of course content as we join with ten students who will be taking Learning from YouTube from within the California Rehabilitation Center at Norco, one of the few places in America (and perhaps the world) where access to YouTube (and other social media networks) is denied to human beings as a condition of their punishment ...

Learning from YouTube was developed to mirror (and therefore make visible) the structuring principles of the site under investigation. Hyper-visibility, user-generated content, the collapsing binaries of public/private, education/entertainment, expert/amateur, and the corporatization and digitization of education, are only few of the site's structures that are also reflected in the course's design and implementation. Another critical framework for the course, like YouTube, was the hidden if also user-desired structures of discipline deeply architected into the experience.

Learning from YouTube Inside-Out has different walls, disciplining systems, and channels of access and visibility that will structure its pedagogy. It is my hope that this will reveal logics of and connections between the prison and social media. A new avenue of thought for me:

What are the relations between social justice and social media?

What are the relations between social injustice and social media?"

Importantly, in the two classes I did get to teach at Norco, my fellow-instructors, students, and I began to understand a critically unnamed truth about social justice and social media only made visible through the structuring denial of access to the Internet and other technology as a fundamental feature of contemporary punishment: technologies of care, conversation, and personal liberation through education need no more tools than access to each other. I was more than ready and able to teach about YouTube this Spring without an Internet connection. I was going to assign books on the subject (with a few pages excised, mostly due to their discussion of sexuality on YouTube), exercises where prisoners would write screenplays to be shot by their fellow-students who had access to cameras and the Internet, and conversations about the meanings of all of our varied and regulated access to technology. (Along this vein, prisoners' near universal access to cellphones as a contraband of choice, despite prisons' concerted efforts to keep phones out of the prison, radically underlines what it means to say "prisoners don't have access to the Internet or social media.") I had learned before that while the prison and its administrators can systematically strip me, and my students, of tools and technologies (pens, videos, the Internet), our desires and abilities to communally learn—and thereby escape its lines, signs, limits, and holes of available information, if only fleetingly—falls completely outside the of logic of technology-based punishment.

That is until I was denied access to teach and learn inside.

Which gets me to my conclusion: my situated critique of education and technology outside the prison, particularly on YouTube. For I am indeed teaching the class, again, for the fifth time since 2007 at Pitzer College. I did not get to stretch and learn and teach as I had hoped with my prisoner students who have so much to teach us about technology, as they are denied access to social media and are therefore uniquely situated to see it, but I have learned about social media and social justice this semester from other students and teachers.

Since I began teaching the class in 2007, in the matter of just these few short years, access to social media has exploded (for those not denied it as a condition of their punishment). We have been told (and sold) that this access is critical for our expression, community-building, political citizenship, and well-being. We have been led to believe that access to social media is a form of liberation. As Nicole Rufus, a current LFYT student explains in her class video below, YouTube matters because it has made her a better person and contributed to her education, just as Lennon suggests.

But two more related things have also become quite clear in the 2015 iteration of the class Learning from YouTube (sans prisoners):

1. In contra-distinction to the experience of prisoners, for my students, the Internet is the very air they breath in a way that was simply not true in 2007 (as much as my students thought it was). Young people today (as is true of their teachers) inhabit the Internet, speak its language, and have an agility, familiarity, and jaded acceptance of its norms and (aspects of) its history that is at once stunning and enervating (see Samantha Abernathey's class video on memes below):

Stunning is the speed and complexity of this familiarity; enervating is its occlusion of familiarity with and interest in the other norms, places, and histories that we might once have understood as part of being institutionally, culturally and personally "situated." The current version of the course makes me feel at once stimulated and enervated because I have seemingly nothing and everything to teach them. Nowhere and everywhere to go. "The internet does not exist." Maybe it did exist only a short time ago, but not it only remains as a blur, a cloud, a friend, a deadline, a redirect, or a 404. If it ever existed, we couldn't see it. Because it has no shape. It has no face, just this name that describes everything and nothing at the same time. Yet we're still trying to climb on board, to get inside, to be part of the network, to get in on the language game, to show up in searches, to appear to exist."

I long for the views of my prisoner students: humans who can teach us a thing or two about place, liberation, punishment and control sans the Internet.

2. For, this place of liberation, the Internet, has quickly become its opposite ("emancipation without end, but also without exit" according to Aranda, Wood, and Vidokle)—a prison (although not a punishment, as it is always entered willingly and ever with the promise of pleasure); a highly-structured corporate-dominated sink-hole. "In the past few years many people—basically everybody—have noticed that the internet feels awkward, too. It is obvious. It is completely surveilled, monopolized, and sanitized by common sense, copyright control, and conformism. (Hito Steyerl)

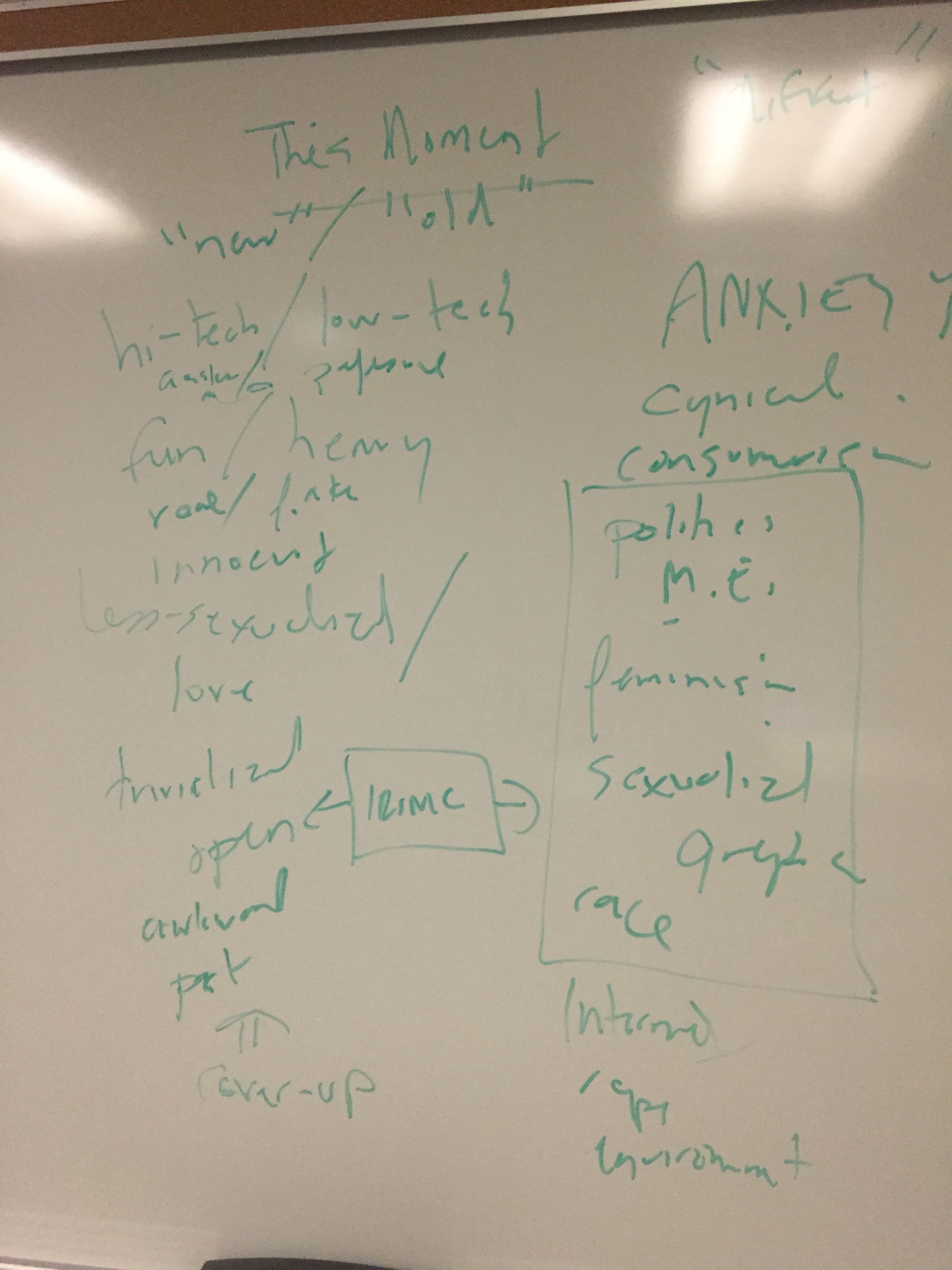

"This moment," according to my students, is defined by anxious, cynical, consumption-based Internet experience that is linked to ever more desperate Internet-based attempts at escape into a nostalgic ("old") Internet time and place that is imagined as low-tech, slow, user-made, fun, real, innocent, awkward, less-sexualized, and de-politicized (outside or before the petty, bitter Internet "politics" about the Middle East, feminism, racism, rape, and the environment from which escape deeper into the Internet is desperately needed.) The new Internet is a prison from which escape is to fantasy of an older, innocent Internet.

In her contribution to the eflux journal issue "The Internet Does Not Exist," from which I've been quoting extensively in this last section, video artist Hito Steyerl pens an article entitled "Too Much World: Is the Internet Dead?" There she answers herself: "the internet is probably not dead. It has rather gone all out. Or more precisely: it is all over."

In her contribution to the eflux journal issue "The Internet Does Not Exist," from which I've been quoting extensively in this last section, video artist Hito Steyerl pens an article entitled "Too Much World: Is the Internet Dead?" There she answers herself: "the internet is probably not dead. It has rather gone all out. Or more precisely: it is all over."

But of course, Steyerl knows, as must we all, that while the Internet feels like it is the whole world, or perhaps too much world, there are blank spots on the map where the Internet can not see, there are ways not to be seen, and there are dark spots in our situated communities where the Internet can't or perhaps is not allowed to go.

If we theorize the Internet, or education, from these blank spots, from the place of too-little, (in)access, quiet, and darkness (as does Lennon), we see values, uses, and needs for MOOCs, YouTube, technology, and education that are not clear from an anxious state of hyper-abundance. This is not to romanticize the punitive lacks of the prison. Rather I ask us to draw from what becomes visible when we situate thinking about learning, technology, punishment and escape in places where education is not primarily linked to tawdry pop-songs, tutorials, consumer goods, flame wars, and self-reference to Internet culture but rather to the fundamental questions of liberation, learning, and empowerment that those stripped of technology have unique access to in the quiet and (in)access of their punishment.

If we theorize the Internet, or education, from these blank spots, from the place of too-little, (in)access, quiet, and darkness (as does Lennon), we see values, uses, and needs for MOOCs, YouTube, technology, and education that are not clear from an anxious state of hyper-abundance. This is not to romanticize the punitive lacks of the prison. Rather I ask us to draw from what becomes visible when we situate thinking about learning, technology, punishment and escape in places where education is not primarily linked to tawdry pop-songs, tutorials, consumer goods, flame wars, and self-reference to Internet culture but rather to the fundamental questions of liberation, learning, and empowerment that those stripped of technology have unique access to in the quiet and (in)access of their punishment.

Image References

1. Inmates watching television at Angola State Penitentiary, Louisiana, 2002. Credit Gilles Mingasson/Getty Images

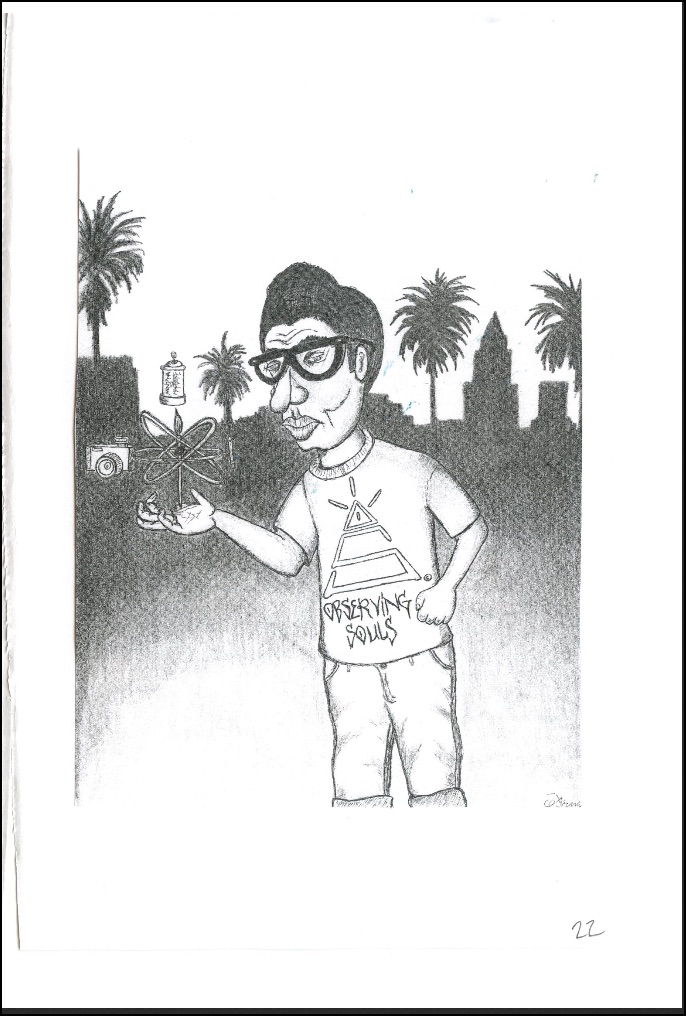

2. Prisoner student's self-portrait of a possible future made during a visualization workshop with visiting professor for Technology in the Prison, artist Sheila Pinkel.

3. "This Moment" as defined by LFYT 2015

4. Abu Ghraib Prison: The infamous Iraqi prison where Saddam Hussein held political prisoners, and where U.S. soldiers were later caught torturing inmates. http://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-2524082/All-US-Armys-secret-bases-mapped-Google-maps.html